On this page...

Over the last 25 years, roundabouts have been used across the United States to reduce crashes, traffic delays, fuel consumption, air pollution, and maintenance costs.

Roundabouts are specifically designed for urban, suburban, and rural locations to accommodate various vehicle types.

Traditional Intersection to Single-lane Roundabout Intersection

Back to topHow Roundabouts Work

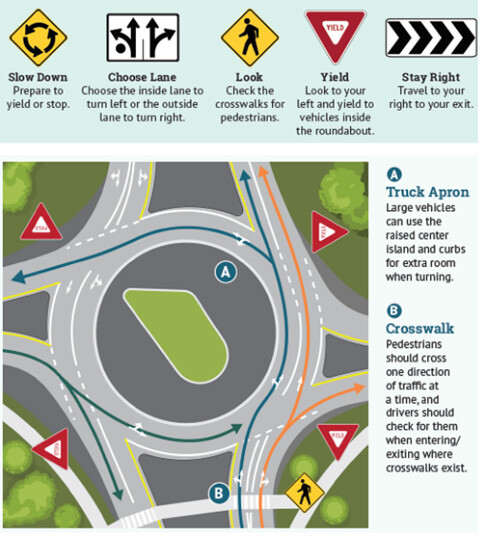

At a roundabout, entering traffic slows down, looks for pedestrians at the crosswalk, and yields to circulating traffic from the left. Once in the roundabout, drivers follow the circle to the right (counterclockwise direction) until reaching their exit.

Most roundabouts in Iowa are single-lane roundabouts. Some roundabouts are on multilane divided roadways. See below for instructions that summarize both types.

Back to topWhy Roundabouts Work

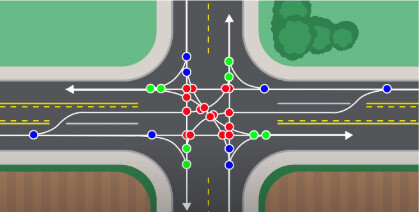

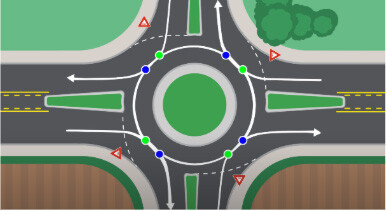

Roundabouts improve safety. Conflict points are locations where vehicle paths cross. Roundabouts reduce the number of conflict points, and especially remove the most dangerous kind of conflict points: left-turn conflict points.

In addition, since roundabouts affect the speed and approach angles entering vehicles, when crashes do occur, they are typically less severe than a two-way stop intersection or a signalized intersection. For these reasons, roundabouts reduce all crashes by 40% at single-lane roundabouts and reduce fatal and severe injury crashes by 80% at single-lane and multilane roundabouts.

Typical Intersection – 32 conflict points | Single Lane Roundabout – 8 conflict points |

|---|---|

|

|

Roundabouts are often the most efficient alternative. The Yield control creates gaps for traffic to enter and reduces wait times compared to a two-way stop intersection and reduces stops during busy (and especially less busy) times compared to an all-way stop intersection or a traffic signal.

Roundabouts are designed for various vehicle types. Roundabout lane widths are wider than normal lanes, and these lanes accommodate cars, buses, and most small trucks that are turning or traveling straight through, as well as large trucks traveling straight through. Larger turning vehicles have a mountable central island (truck apron) and sometimes additional mountable areas on the corners, for off-tracking wheels.

Roundabouts are often constructed near schools. This is due to typical school “peak” traffic periods in the morning and afternoon, as well as the ability for roundabouts to simplify pedestrian crossings of one direction at a time. A variety of roundabouts have been constructed near schools in Iowa, including these examples:

| City/County/ School District | Schools | Map Link |

|---|---|---|

| Cedar Rapids – Linn County – College CSD (Prairie HS) | Complex serves 8 schools (Pre-K through HS), a bus barn, and sports complex | Google Maps |

| Gilbert – Story County – Gilbert CSD | Between Intermediate, Middle, and High School. Connects City and Co-op to US 69 | Google Maps |

| Fayette County – Starmont CSD | Rural intersection near combined Elementary, Middle, and High School | Google Maps |

| Johnston – Polk County – Johnston CSD | Suburban High School campus | Google Maps |

| Orange City – Sioux County – MOC-Floyd Valley CSD | Urban/Rural transition of medium sized city. New Elementary to south, HS and college to west. |

|

Waukee – Dallas County – | Suburban. Between Waukee MS and Waukee HS. Serves Bus entrances. | Google Maps |

Where are Roundabouts in Iowa and Where is Iowa DOT Constructing Roundabouts?

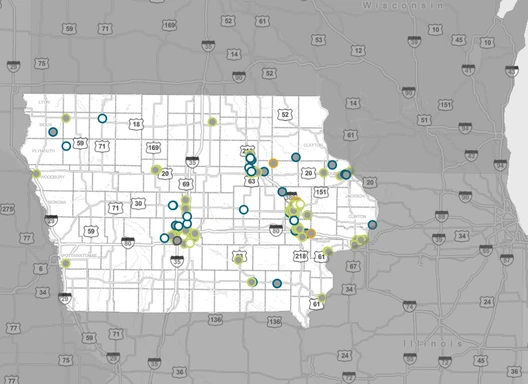

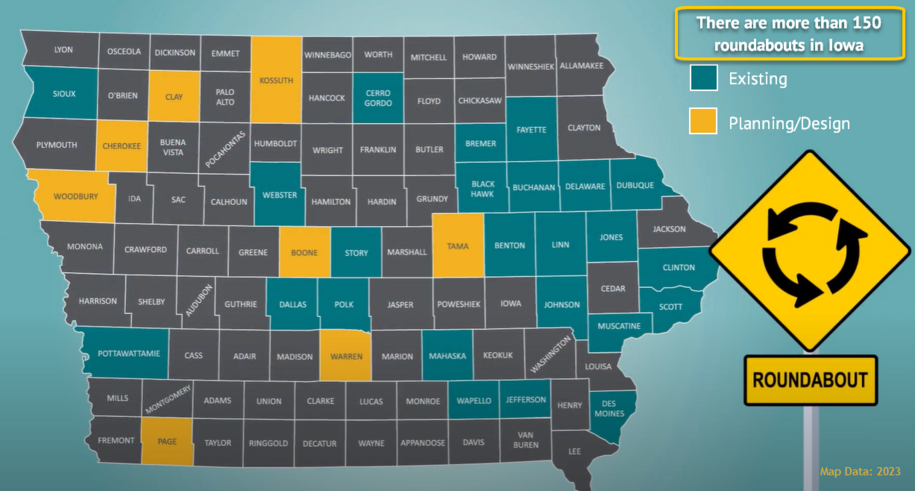

Iowa has over 150 roundabouts across the state, with 10-15 new roundabouts constructed each year since 2015. Approximately 20 roundabouts are on Iowa DOT’s Primary highway system, with more are in different stages of planning, design, or construction.

As a comparison, the State of Iowa has approximately 115,000 paved intersections, with about 15,000 of those on the state Primary highway system. Roundabouts currently make up about one out of every 1,000 paved intersections.

The map and link below show an inventory of Roundabouts in Iowa – on the Primary (State) Highway System, Secondary (County) Roads, and Municipal (City) Streets.

Roundabouts are being constructed around the World, the USA, and the Midwest. Follow these links for more information:

- Federal Highway Administration – Proven Safety Countermeasures

Insurance Institute of Highway Safety (IIHS) –

Studies on safety, efficiency, public opinion before/after construction

Iowa State University Institute for Transportation

2008 Roundabout Guidance for the Iowa DOT

- Roundabouts in Minnesota

- 2017 A Study of the Traffic Safety at Roundabouts in Minnesota

- Roundabouts in Wisconsin

- Roundabouts in Missouri

- Roundabouts in Nebraska

- Roundabouts Around the World – Inventory Map (Kittleson & Associates)

Programs and Contacts

Complimentary Roundabout Design Review Service

The Iowa Department of Transportation offers no-cost, expert roundabout reviews during the feasibility, planning, design or operation of roundabouts in Iowa. The DOT is presently using two nationally-known and respected roundabout consulting firms to help ensure early success for roundabouts in Iowa. See the Complimentary Roundabout Design Review Service brochure.

Traffic Engineering Assistance Program (TEAP)

The Complimentary Roundabout Design Review Service is funded through the Iowa DOT Traffic Engineering Assistance Program (TEAP). Cities and Counties can also apply for general TEAP studies for a range of existing traffic and safety issues. TEAP studies identify cost-effective traffic safety and operational improvements as well as potential funding sources to implement the recommendations. Learn more about the Iowa DOT Traffic Engineering Assistance Program (TEAP).

Traffic Safety Improvement Program (TSIP)

The Iowa DOT Traffic Safety Improvement Program (TSIP) provides up to 500,000 for site-specific safety improvement projects based on competitive benefit/cost evaluation. Applications are due August 15. Learn more about the Iowa DOT Traffic Safety Improvement Program (TSIP).

- Iowa DOT District Contacts (Engineering and Planning Staff)

- Iowa DOT Local System Bureau Contacts